My notes on Chapters 2 - 6 of the book Programming Massively Parallel Processors 4th Edition.

CUDA Programming model

- Allocate memory on the GPU device to hold the data we want to compute on

- Copy data from host memory to device memory

- Perform the parallel computation

- Copy results from device to host memory

void vecAdd(float* A, float* B, float* C, int n) {

float *A_d, *B_d, *C_d; // suffix _d is naming convention for data on the device as opposed to host

int size = n * sizeof(float);

// 1. allocate memory on the GPU device

cudaMalloc((void **) &A_d, size);

cudaMalloc((void **) &B_d, size);

cudaMalloc((void **) &C_d, size);

// 2. copy memory from host to device

cudaMemcpy(A_d, A, size, cudaMemcpyHostToDevice);

cudaMemcpy(B_d, B, size, cudaMemcpyHostToDevice);

// 3. launch the vector add kernel with n/256 blocks and 256 threads per block

vecAddKernel<<<ceil(n/256.0), 256>>>(A_d, B_d, C_d, n);

// 4. the result will be stored in C_d, so we copy it from GPU device to host memory

cudaMemcpy(C, C_d, size, cudaMemcpyDeviceToHost);

// free the memory on the device now that we are done

cudaFree(A_d);

cudaFree(B_d);

cudaFree(C_d);

}

What is a grid? What is a block?

- Grid: when we call vecAddKernel, we are launching a "grid of blocks"

- Block: each block contains a bunch of threads

- Thread: a thread is an instance of the running kernel code

The values in the <<< and >>> define the execution parameters.

The first value defines how many blocks are in the grid and the second defines how many threads in each block.

The grid is a 3D array of blocks. Each block is a 3D array of threads.

dim3 dimGrid(32, 1, 1);

dim3 dimBlock(128, 1, 1);

vecAddKernel<<<dimGrid, dimBlock>>>(...);

CUDA has built in variables blockIdx and threadIdx to help each thread differentiate themselves.

int tx = threadIdx.x; int ty = threadIdx.y; int tz = threadIdx.z;

int bx = blockIdx.x; int by = blockIdx.y; int bz = blockIdx.z;

We use the block id and thread id to compute the indicies we want to access in our input arrays.

__global__

void vecAddKernel(float* A, float* B, float* C, int n) {

int i = threadIdx.x + blockDim.x * blockIdx.x;

if (i < n) {

C[i] = A[i] + B[i];

}

}

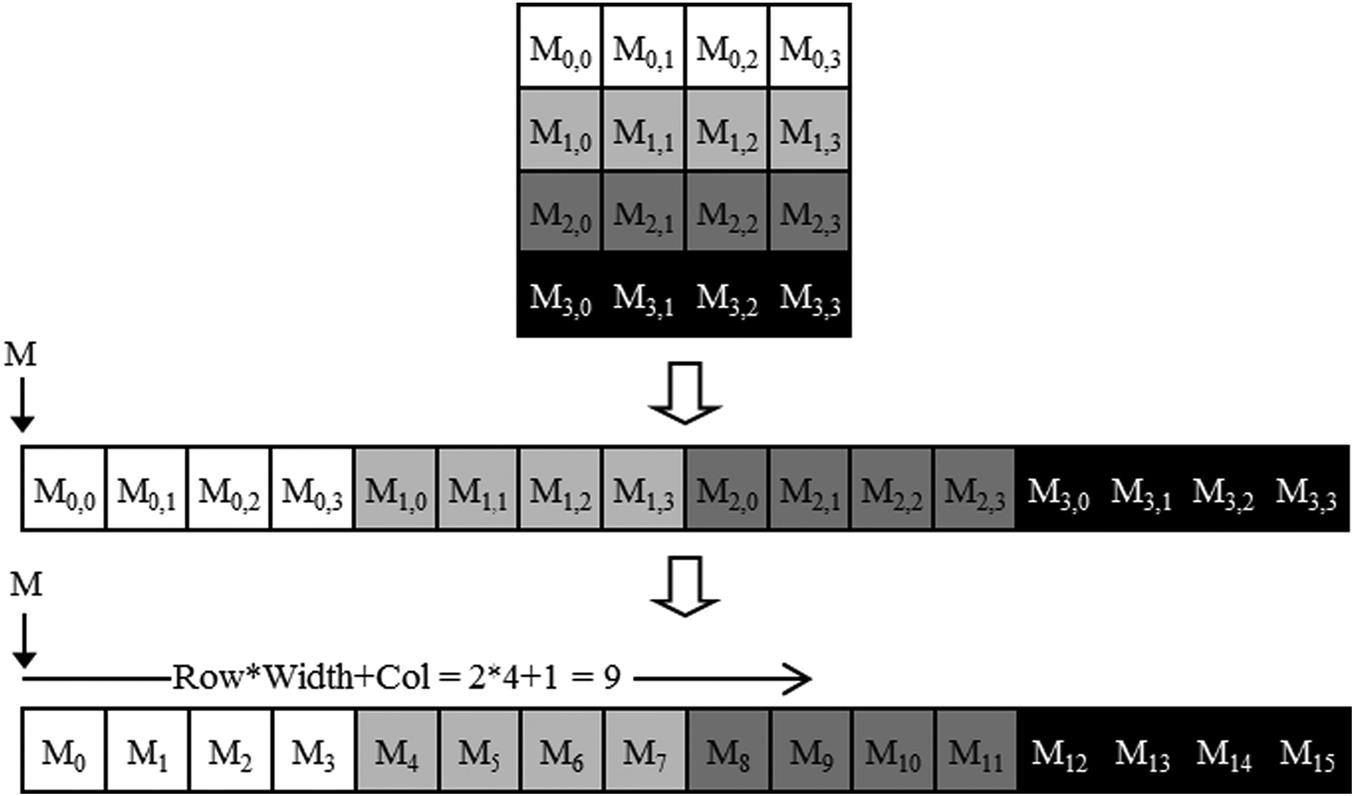

How is the data stored in memory?

For a 2D array, you can linearize in row-major or column-major format.

Here is an example matrix multiply kernel where inputs and outputs are in row major format.

__global__ void MatrixMulKernel(float* M, float* N, float* P, int Width) {

int row = blockIdx.y * blockDim.y + threadIdx.y;

int col = blockIdx.x * blockDim.x + threadIdx.x;

if ((row < Width) && (col < Width)) {

float Pvalue = 0;

for (int k = 0; k < Width; ++k) {

Pvalue += M[row * Width + k] * N[k * Width + col];

}

P[row * Width + col] = Pvalue;

}

}

Note that row is computed using the y values and col computed with x values.

Indexing into row major layout:

Arr[row][col] --> Arr_linear[row * width + col]

What happens at the hardware level?

Each CUDA capable GPU has a bunch of streaming multiprocessors (SMs).

Each SM has several CUDA cores. Example: A100 has 108 SMs with 64 cores each.

All threads in the same block run on the same SM.

Threads in the same block can interact with each other via shared memory and barrier synchronization.

Threads in a block are scheduled as warps.

What is a warp? What is occupancy?

Warp: a collection of 32 threads with consecutive threadIdx values that run in parallel on an SM.

If a block has 256 threads, then it has 8 warps. If 3 of these blocks are assigned to an SM at once, then that SM has 24 warps.

Occupancy: # of threads assigned to an SM / maximum # of threads

We usually want to maximize occupancy to take advantage of latency tolerance.

When an SM has many warps/threads assigned to it, it's more likely to find a warp that isn't waiting on a long latency operation.

It can execute this warp while other warps are waiting, which helps us maximize hardware utilization.

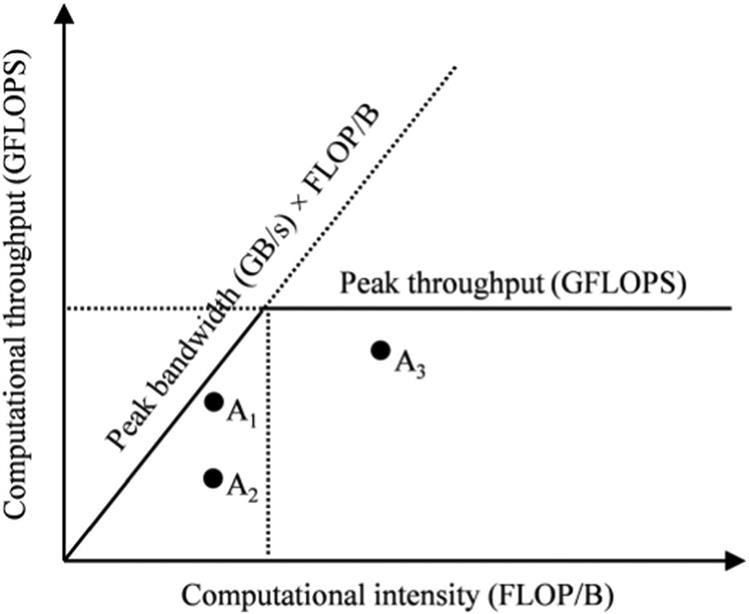

How to know if my kernel is actually fast?

Arithmetic Intensity: ratio of FLOPs performed for each byte access from global memory

Each application has a computational/arithmetic intensity that is defined by your compute algorithm and your kernel implementation.

We can identify where we have room to improve by analyzing our application with a roofline model.

Memory bound: your application is bottlenecked by memory bandwidth. (eg. points A1 and A2 that are under the diagonal)

- Comparing A1 vs A2, A2 has more room to improve efficiency of memory bandwidth usage.

Compute bound: your application is limited by the hardware's peak computational throughput. (eg. point A3)

- For A3, we may explore how to be more efficient with our usage of compute resources.

CUDA memory types

There are many different CUDA memory types. Most relevant ones are registers, shared memory, and global memory.

Registers are on chip memory that are allocated to individual threads.

Shared memory is on chip memory that can be accessed by all threads on the same block.

Global memory is typically off chip DRAM, can be accessed by host and all device threads. It has long access latency (hundreds of clock cycles).

Tiling

Accesses to global memory are slow so we want to reduce them as much as possible.

One technique we can use is tiling, where we partition the data into subsets (aka tiles) that fit into shared memory.

Threads of the same block can work together to fetch and use the data in shared memory.

for (int k = 0; k < Width; ++k) {

Pvalue += M[row * Width + k] * N[k * Width + col];

}

In our naive matrix multiply kernel above, each thread is doing 2*Width global memory accesses.

Instead, we can use tiling to reduce the amount of global memory accesses by TILE_SIZE.

Phase 1: Load M tile (0, 0) and N tile (0, 0) into shared memory.

Accumulate partial products into P tile (0, 0)

Here, each thread does only 4 instead of 8 global memory accesses (2 accesses per phase).

// EXAMPLE TILED MATRIX MULTIPLY KERNEL

#define TILE_WIDTH 2

__global__ void matrixMulKernel(float* M, float* N, float* P, int Width) {

__shared__ float Mds[TILE_WIDTH][TILE_WIDTH];

__shared__ float Nds[TILE_WIDTH][TILE_WIDTH];

int bx = blockIdx.x; int by = blockIdx.y;

int tx = threadIdx.x; int ty = threadIdx.y;

// --- ROW AND COL OF OUTPUT P TO WORK ON ---

int Row = by * TILE_WIDTH + ty;

int Col = bx * TILE_WIDTH + tx;

// --- LOOP OVER THE M AND N TILES TO COMPUTE OUTPUT ---

float Pvalue = 0;

for (int ph = 0; ph < Width / TILE_WIDTH; ++ph) {

// --- COLLABORATIVE LOADING OF M AND N TILES INTO SHARED MEM ---

Mds[ty][tx] = M[Row * Width + ph * TILE_WIDTH + tx];

Nds[ty][tx] = N[(ph * TILE_WIDTH + ty) * Width + Col];

__syncthreads();

// --- COMPUTATION LOOP ---

for (int k = 0; k < TILE_WIDTH; ++k) {

Pvalue += Mds[ty][k] * Nds[k][tx];

}

__syncthreads();

}

P[Row * Width + Col] = Pvalue;

}

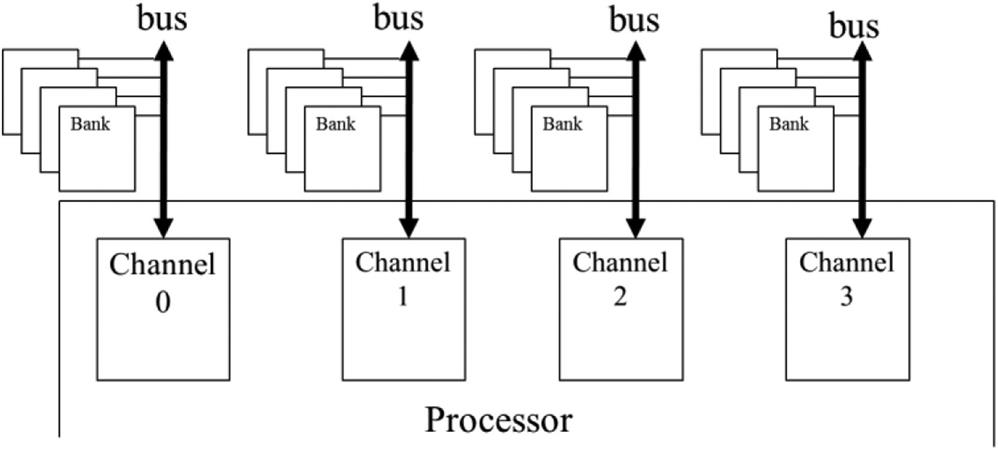

Memory hardware (channels and banks)

Memory cells are stored in banks.

A channel connects to multiple banks.

Multiple channels connect the memory to the processing chips.

Peak GPU memory bandwidth is the sum of bandwidth of all it's channels.

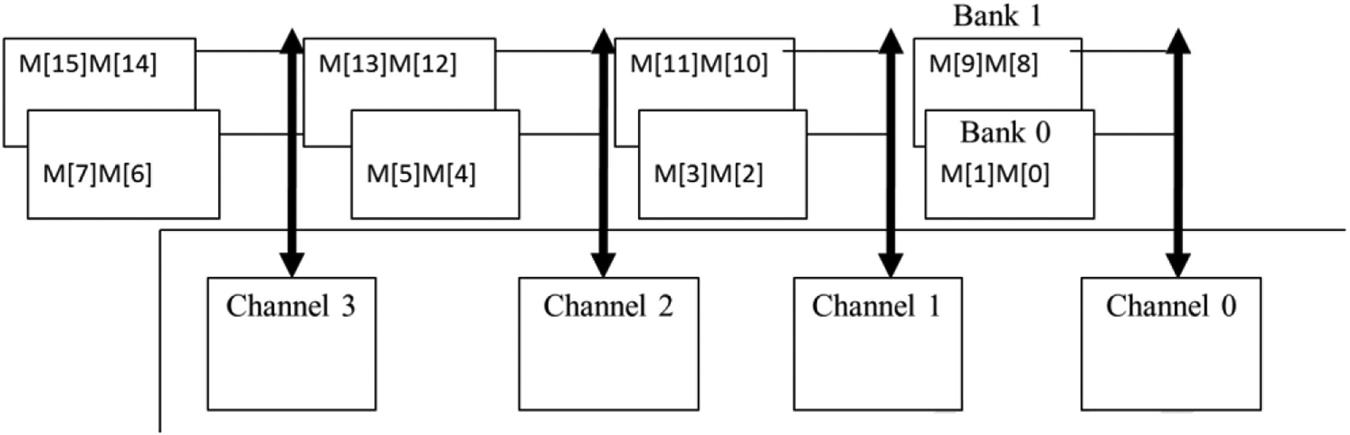

Memory coalescing

A bank can process a single memory transaction at a time.

A warp issues one or more memory transactions when its threads access global memory.

If the addresses are contiguous and aligned (e.g. thread 0 reads A[i], thread 1 reads A[i+1], ...), the accesses can be serviced with fewer, larger transactions.

If the addresses are scattered or misaligned, the warp needs more transactions, which wastes bandwidth.

We can improve coalescing by choosing data layouts (row major vs col major) and thread-to-data mappings so that threads in the same warp access consecutive elements.

The channel/bank topology sets the bandwidth ceiling; coalescing determines how efficiently your kernel uses it.